ARUP Marks the Milestones of Its 40-Year History

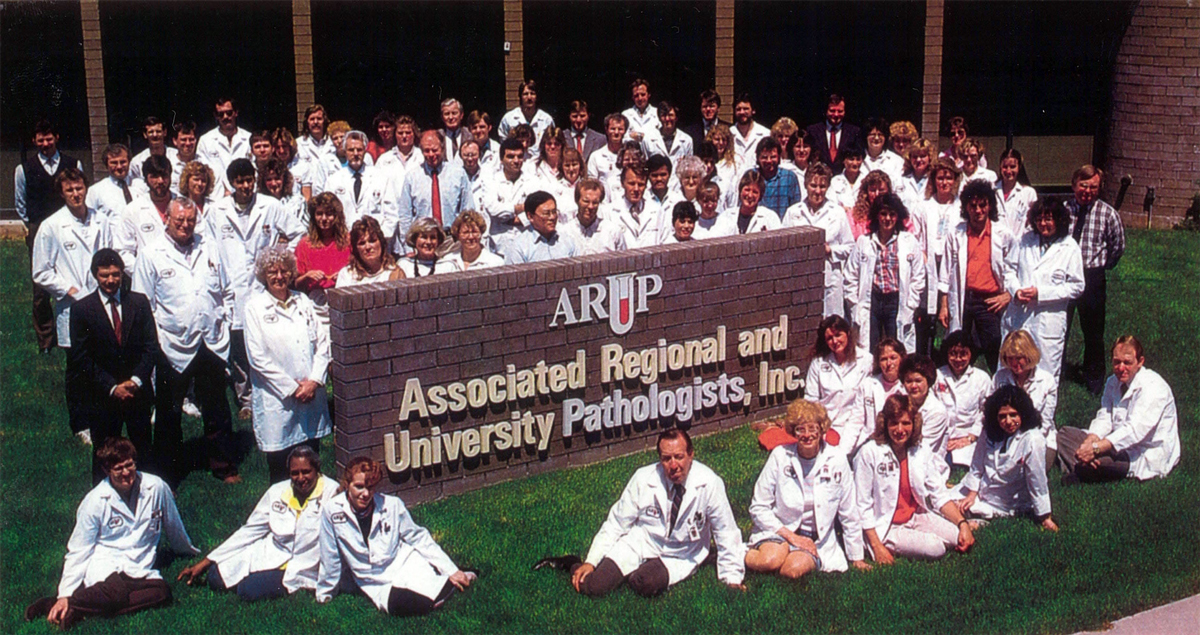

Associated Regional and University Pathologists Inc. formally launched on June 15, 1984, the day lab employees received pink slips from the University of Utah Hospital that a lab secretary filled out by hand.

Watch ARUP's founders and current leaders reminisce about the early days and celebrate what's to come.

June 1984

Associated Regional and University Pathologists Inc. formally launched on June 15, 1984, the day lab employees received pink slips from the University of Utah Hospital that a lab secretary filled out by hand.

“The way it was presented was as such an opportunity, such a journey, and such a great experience that I don’t know if I was as nervous about it as I should have been at the time, but I was one of the lucky ones to get that pink slip,” said Leslie Hamilton, MT(ASCP)SM, former senior vice president of Technical Operations.

The group of about 100 immediately joined a new company now known as ARUP Laboratories, but the idea was born more than a decade earlier when Lloyd Martin became the business manager for the university’s Department of Pathology. He promoted the concept of pathologists owning and operating a reference laboratory. Within a year of Martin’s hiring, John M. Matsen, III, MD, would return to his native Utah to accept a professorship in pathology and pediatrics at the U School of Medicine and to direct the U’s clinical laboratories. Matsen would become the driving force to persuade the faculty to embrace the unique business venture, which was not an easy sell. He had to convince career state employees with attractive retirement packages, job security, and little business experience to join a for-profit testing lab.

“All of our employees were scared to death. They were going to lose their regular insurance, and they didn’t know what was going to happen with their retirement through the University of Utah, but John Matsen was convinced ARUP would succeed,” Harry R. Hill, MD, an ARUP founder, reminisced.

Matsen also needed the hospital’s support, which was an easier sell, thanks in part to new federal regulations capping lab fees. The administrators saw the practical side of the lab splitting off from the hospital, especially given their anxiety over potential shortfalls from lab fees.

The small startup moved out of the U Hospital in August 1984 and into an old Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) lab at 390 Wakara Way in Research Park, complete with turrets, like a castle.

Caravans of moving vans and pickup trucks transported each lab’s equipment over three days, but it would take months to complete the move. During that time, not a single item was damaged or lost, and no tests were interrupted.

“We kind of predicted, those of us who started with ARUP, that within a couple of years we’d probably be moving back, so we didn’t worry, and things just continued to grow. I would have never imagined we would be in the position we are today,” said Nancy Andes, MBA, MT(ASCP), former senior vice president of Marketing.

Space was tight in the 25,000-square-foot building in those early years, and employees developed a sense of humor and of family. Several office romances developed, 59 of them resulting in marriage. Employees wore many hats. They shoveled snow in the winter, mowed the lawns and trimmed trees in the summer, and used their own cars to transport specimens.

"We had a dream when we started it. It was a little bitty lab in a little bitty building. People were very concerned about moving away from the university, but we survived, and we worked hard and took chances. We had fun doing it,” Hill said.

1989: Intermountain Healthcare Becomes a Client

ARUP did not have a model to guide its growth and overcame many hurdles in the first few years, including merging academia with business, learning to keep pace with the competition, and convincing clients outside the Intermountain Region that it could handle sophisticated tests. As ARUP’s first president, Matsen encouraged his staff to expand and often took to the road himself to sell ARUP’s unique services to clients, many times after an all-nighter in the lab. His colleagues said he either slept on the plane or in his mint-green trailer parked behind the hospital.

ARUP’s selling points far outweighed its weaknesses. As a medical school lab with sophisticated technology capable of providing high-quality, cost-competitive, full-service esoteric testing, ARUP openly shared its knowledge, technology, and expertise.

“Our focus was to help our clients,” Hill said. “If they wanted to bring on a test that we were doing, we would help them set it up.”

“If you look at what we did in helping others, sometimes it was detrimental to our growth because we helped them make their labs successful. It played into our values, our mission, and our goals as an educational facility as well as a reference laboratory,” Andes said.

ARUP won the business of several academic medical centers, including the University of Minnesota and the University of Washington. Their endorsements paved the way to more growth and proved that ARUP was a legitimate player in the reference laboratory business. But perhaps one of the biggest shots in the arm came in 1989, when Intermountain Healthcare signed a 10-year contract with ARUP. Intermountain’s flagship facility, LDS Hospital, was already using ARUP for routine testing. The head of pathology there had given approval for the hospital and its renowned Primary Children’s Hospital to send some testing to ARUP in previous years.

CEO Andy Theurer said it was a sought-after contract, but a tricky one. “We are part of the University of Utah, yet we are going to try to service one of the university’s biggest competitors. It worked out beautifully because it gave us the amount of work we needed to develop very sophisticated testing, and from that moment we really moved from a regional lab to a national one.”

Eventually, Intermountain became one of ARUP’s largest clients, nearly every hospital in Utah came to rely on ARUP, and “regional” in ARUP’s name no longer applied to the company. ARUP had clients, including academic medical centers, pediatric hospitals, and teaching hospitals, in all 50 states, making it a national reference laboratory.

1992: Matsen Leaves To Become U VP, Kjeldsberg Takes Over

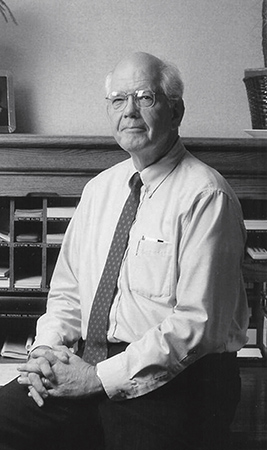

Matsen pushed his staff and managers hard to ensure ARUP’s success. He is famous for pointing his index finger in a way that (he said) meant emphasis. Those working with him knew the pointing finger meant, “Just get it done.”

“Without John Matsen, we would never have [had] an ARUP. … He was so important, so brave, and was a real driver,” said retired CEO Carl R. Kjeldsberg, MD.

Matsen’s absolute commitment, high expectations, willingness to work with others, generosity, and mentorship shaped what ARUP is today.

“He was a teacher at heart,” Hamilton said. “He wanted the very best from all of us and spent a lot of time in the lab before he became so busy. He was always focused on quality.”

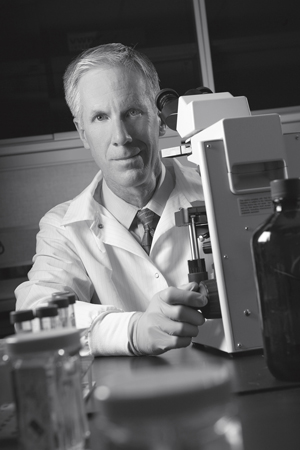

In November 1992, Matsen stepped down as ARUP CEO and U Department of Pathology chairman to become the U’s vice president of health sciences. Kjeldsberg took over leadership at ARUP with his own unique style and profoundly influenced ARUP culture.

“Carl was a big proponent of work-life balance. In the early years, he used to take Wednesday afternoons off during the ski season, and he would hold a board meeting at Snowbird, on skis—a board meeting,” said Ronald Weiss, MD, MBA, former president and chief operating officer.

Kjeldsberg’s philosophy was, “Hire the best, treat them well, and they will treat the customers well.” He is famous for “walkabouts” around the labs and Wednesday walks in Red Butte Garden with employees for exercise and conversation.

“I practiced management by walking around. I did not want to isolate myself in the office. That is how a CEO fails. I needed to go into the trenches to see what [was] happening, and I would often hear things that I would have never heard if I was sitting in my office,” Kjeldsberg said. “I also emphasized that employees needed a balanced lifestyle.”

Kjeldsberg challenged ARUP to start a daycare, to provide excellent tuition and health benefits, and to create an on-site health clinic for employees and their families, all of which continue today.

The 5 Pillars of ARUP Culture

ARUP first articulated its core values in writing as part of the strategic planning that led to its expansion in the early 1980s and eventual evolution into a nationwide reference lab, Weiss said. He was among the leaders who translated ARUP’s vision and mission statements into the Five Pillars, which he described as an effort to crystalize and codify ARUP’s culture into bullet points that people could recognize in what they were doing and use as a guidepost. Those bullet points, now known as The Five Pillars of ARUP Culture, include:

- Provide excellent patient care by supporting clients.

- Create a good working environment.

- Do the right thing.

- Improve continuously.

- Act responsibly.

“Each one of them was important in supporting the overall mission of quality healthcare, research, and education, but primarily a focus on patient care,” Weiss said. “As long as we act in the interests of patients and employees, continue to improve individually and as an organization, and we’re fiscally responsible, that is still a formula for success.”

The Five Pillars have stood the test of time and guide the decisions that leaders at ARUP make, said Sherrie L. Perkins, MD, PhD, who served as CEO from 2017 to 2021. “Academics and trying to do the right thing drive so much of what we do. The Five Pillars distill core values that make sense from a business and an ethical perspective.” The mission is clear, and the company’s actions align with it.

ARUP has a reputation among employees and others as one of the best places to work in Utah and is ranked among Forbes magazine’s Best Employers by State. Utah Business magazine has honored ARUP with a “Best Companies to Work For Award” every year since 2018. The award measures employee satisfaction related to culture, benefit offerings, and compensation.

“One of the most important things that we do here is treat our workforce well, so they can turn around and forward that treatment on to the patients and the doctors,” said Theurer, the CEO.

1994: Medical Directors Freed From Responsibility for Lab Operations

By the mid-1990s, ARUP’s business was thriving. Nearly two-thirds of the nation’s academic health centers were sending samples to ARUP, including Stanford, University of Pennsylvania, and Harvard, and the company was focused on growth after four years of substantial profitability. Then came some bad news—an $800,000 loss in March 1994. Theurer, who was the assistant controller at the time, said, “We had hired too many people too quickly. We still didn’t know how to operate a profitable business.”

ARUP officers gathered the technical operations managers and ordered them to develop standards for lab and department staff sizes, as well as staff titles, and to implement new efficiencies. The result was a historic power shift that moved operational logistics from the medical directors to the technical operations managers, and a quick return to black ink.

“So many people see this as a watershed moment for ARUP. The medical directors were moved into areas of expertise where they were absolutely needed and out of the day-to-day running of the company. We developed a lot of processes that decreased costs and were good for all the labs,” Hamilton said.

Hill, seeing a need to support the medical directors, founded the ARUP Institute for Clinical and Experimental Pathology® to help maintain an emphasis on publishing research, developing new tests, and embracing emerging technologies.

“Harry was probably the one individual who has had the biggest impact on preserving the academic nature of ARUP. He consolidated research and development into one unit. R&D is central to what we do as a reference lab. You need to look at the future, develop tests, get them into production in our clinical laboratories, and provide them for the people we serve across the country,” said Peter Jensen, MD, chairman of the U Department of Pathology and the ARUP Board of Directors.

Around this same time, a sendout supervisor at a Texas hospital complained about ARUP’s downtime and said that ARUP needed to move to 24/7 operations to compete with the “big boys.” ARUP employees mostly went home in the late evenings and on weekends, but hospitals were under increasing pressure to keep patient stays to a minimum, meaning they needed lab results fast. Another physician in California complained that no one at ARUP was answering the phone on July 24.

“The head of Marketing, Don Wood, picked up the phone, and there was an angry voice saying, ‘Why are you not answering the phone? I’ve been calling for almost a half-hour.’ Wood said it was Pioneer Day (a Utah state holiday), and the physician said, ‘We don’t have Pioneer Day here, and unless you guys get your act together, I’m not going to send any specimens to ARUP.’ From that day on, we worked every day,” Kjeldsberg said.

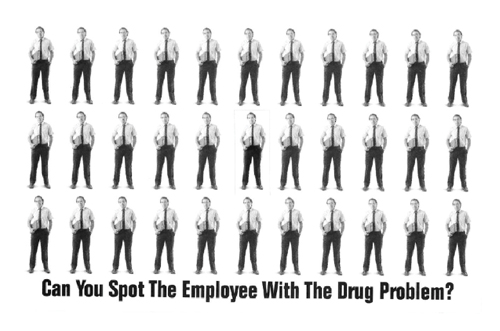

1999: ARUP Exits the Corporate Drug Testing Business

Throughout the years, although some business ventures worked well, leaders eventually decided that others did not fit ARUP’s commitment to put patients first. In 1985, ARUP embarked on workplace drug testing for an oil-drilling company that wanted its employees tested for marijuana, and other sectors were becoming interested in drug testing as President Ronald Reagan’s “War on Drugs” was taking off. ARUP was certified to test federal employees for drug use in 1989 and was the 35th lab in the nation to be given this status. Despite performing thousands of tests every month, ARUP’s profit margins on drug testing were small, and its core mission centered on patients’ health, not the corporate world. Ten years after it was created, ARUP would turn over its corporate drug testing business to Northwest Toxicology and refocus on clinical testing.

ARUP was also briefly in the veterinary testing business, but the lab work was difficult. First, veterinarians wanted more detailed analyses of cultures for their horse, cattle, and canine specimens than hospitals were requiring for humans. Second, most of ARUP’s lab instruments were not designed for animal specimens. Finally, the samples came in all shapes and sizes.

“A bird would die, and they would send us the whole bird,” said Peggy Ahlin, former senior vice president, director of Quality and Compliance. “There was a diarrhea outbreak at Hogle Zoo. We got buckets of samples.” Eventually, the animal testing was discontinued.

2001: ARUP Obtains Tax-Exempt Status

ARUP was founded as a for-profit entity, and for the first 16 years, paid taxes. In 1997, the Utah Tax Commission audited the lab, found that ARUP suppliers were not charging sales tax on out-of-state purchases, and said the lab owed $1.3 million from the previous four years.

“We did not have money. We were borrowing money to make payroll,” said Theurer, who was ARUP’s controller at the time and was tasked with fixing the tax bill. Theurer worked with a tax consultant named Glenn Bartholomew, who after six months of research, found a little-known provision in the federal tax code permitting companies to claim a federal income tax-exempt status if they provided an essential government function. Theurer saw an opportunity that aligned with ARUP’s academic research role, teaching mission, and financial commitment to the university, but he had to convince the Executive Committee, whose members did not agree at first, and the university. Theurer eventually received permission to pursue the tax exemption, but it set up a three-year battle with the Internal Revenue Service.

“They sent out three teams of the top brass to shut this down, and every one of them agreed with our assessment. In April 2001, the Internal Revenue Service issued us a rare private letter ruling granting tax-exempt status, and that completely changed the financial complexion of ARUP,” Theurer said.

“It was the start of a fantastic relationship that tied ARUP’s success to the university’s success. We take some of the money we would pay in tax and distribute it to the university,” Theurer explained. “The model has served us well. I meet with the university president once a quarter, and as I tease him, I have several million reasons to meet with him because we give a quarterly distribution at that meeting.”

2002: ARUP Averts a Plan To Sell the Company

Despite ARUP’s nonprofit status and the promise of ongoing revenue to the U, the possibility that ARUP could be sold persisted. University President Bernie Machen, DDS, MS, PhD, considered a sale in late 2000 and hired consultants to determine ARUP’s worth.

“For months, I was carrying this terrible secret. People in dark suits were touring the laboratory. I made them take off their jackets so at least it would not be so obvious to the employees,” Kjeldsberg said.

The attractiveness of a sale lost its luster when the market cooled after the 9/11 terror attacks, and the price dropped 75%. To keep the U from selling ARUP, Kjeldsberg entered a five-year memorandum of understanding with Machen in 2002, giving the president $5 million annually for keeping the company within the university.

The sense of relief did not last long. By January 2003, the venture capital group, Sorenson Capital, was interested in ARUP, and Machen’s legal counsel had determined that the memorandum was not a legally binding document. Kjeldsberg said he was incredibly angry.

“I couldn’t believe it. We had just signed an agreement, and to make things worse, the proposal was loaded with financial incentives for ARUP executives. They wanted to buy me and some of the other executives,” Kjeldsberg said.

ARUP’s mission was to advance laboratory medicine and put patients first, not necessarily to make money. The Executive Committee opposed the sale unanimously, and a very influential ARUP board member resigned in protest, Theurer said.

“Nobody on the Executive team was interested in personal gain on the backs of everybody who built ARUP. I remember having a frank conversation with then-CEO Carl Kjeldsberg, who said, ‘Andy, we need to do everything we can to stop this deal. It is not good for ARUP, the workforce, our patients, the University of Utah, or the state,’” Theurer recalled.

Kjeldsberg and his team made an 11th-hour effort to derail the sale, offering loans and cash to the U. Meanwhile, Machen and the trustees were having second thoughts over the economics of the deal, which would plunge ARUP into debt, and eventually came to the decision that ARUP should be kept under the university’s umbrella. The financial advantages of the tax-exempt status ARUP enjoyed as a university entity would have been lost in a sale.

In April 2003, Machen called Kjeldsberg to say the deal was off, but he wanted a bigger cut from ARUP. He wanted a flat-percent share of annual revenue, and Kjeldsberg reluctantly agreed to the new deal.

2008: Major Real Estate Purchases Secure Building 560 and Expansion of Central Facility

ARUP continued to grow during the early 2000s, adding Building 1.5 in 2003, which included a two-story freezer capable of storing more than 2 million specimens for up to one year. The freezer, still in operation, uses a robotic system and custom software to control access to specimens and their storage trays, reducing the incidence of handling errors and premature discards.

In the fall of 2008, needing even more laboratory space, ARUP purchased a building at 560 Arapeen Drive, moving administrative employees to the new space over the course of a year and freeing up prime lab space in the main facility. Buildings 585 and 606 were purchased around the same time, and ARUP leased what is known as the “Triangle Parking Lot” long term. Theurer said the transactions were strategic, gave the company bargaining power to also purchase the buildings that made up the central facility, and allowed for further expansion.

“In the beginning, we were leasing from a local developer, and that relationship was great. Years later, the buildings were sold to a real estate investment trust, and every time we needed to make changes or remodel labs, which was often, the rent would go up. I built a plan to move the entire campus down to the plot where the Triangle Lot is now—and leaked it. Suddenly, the trust wanted to sell, and now we do not answer to a landlord,” Theurer said. “That also gave us undeveloped land for what became Building 4, and land for future growth.”

4 CEOs in 4 Years

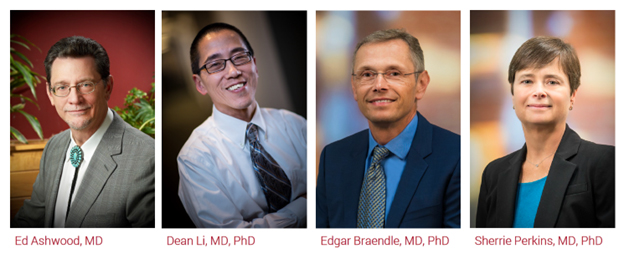

Kjeldsberg retired as CEO in 2009 after more than 16 years as the head of ARUP. Edward R. “Ed” Ashwood, MD, served as president and ARUP’s third CEO until 2015. Then, Dean Li, MD, PhD, stepped into the role as interim CEO until Edgar Braendle, MD, PhD, took over in August 2016. Since ARUP is owned by the U, leaders there had tremendous influence on the leadership at the company.

Vivian Lee, MD, PhD, MBA, the U’s senior vice president of health sciences from 2011 to 2017, wanted a different trajectory for ARUP and chose Braendle, whose background was in the pharmaceutical industry and who had little experience with laboratory testing, to focus beyond lab tests and on medical device creation. Lee also wanted ARUP to consider collaborating with Theranos, the then-darling of Silicon Valley that promised a perfect marriage between technology and healthcare. The now-defunct company claimed it could run hundreds of blood tests from a single, tiny sample, and Elizabeth Holmes, the former CEO, is serving time in prison for fraud.

Lee resigned from the U not long after Braendle’s arrival, and ARUP’s board decided the leader of the company should have extensive experience in laboratory medicine. They chose Perkins, a renowned hematopathologist and already a member of ARUP’s Executive Committee, as CEO, and she wanted a partner at her side.

“I chose Andy Theurer to help me because I didn’t have a lot of business background. I had been an academic my whole life, with a career focused on research, teaching, clinical work, and some administration,” Perkins said. “He and I were able to build a very solid team that did great clinical medicine and combined it with academics and business.”

Perkins was the first woman to serve as CEO of any major reference laboratory. ARUP has since been honored as one of 100 Utah Companies Championing Women, and Forbes magazine included ARUP on its list of the nation’s Best Employers for Women.

2020: COVID-19 Pandemic Changes Everything

In December 2019, a cluster of patients in China experienced the symptoms of a pneumonia-like illness that did not respond well to standard treatments. ARUP closely followed the developments and started working on a test. Under the leadership of ARUP’s chief medical officer at the time, Julio Delgado, MD, MS, ARUP’s medical director of Molecular Infectious Diseases, David R. Hillyard, MD, was instrumental in validating one of the first high-throughput COVID-19 diagnostic tests in the country. Hillyard and his colleagues in R&D validated the test in three days and opened testing on March 12, fast-tracking the normal six- to 12-month validation process.

“Without the expertise of the R&D staff, their familiarity with the process, and their adaptability, validating a test at this speed would not have been possible,” Hillyard said.

“Our quality is extremely important to us. Within two days, the demand from our customers was so high, we could not meet it,” Jensen said. ARUP had to shut down testing, find lab equipment, knock down walls to create space for new labs, and hire staff to deal with the rapidly increasing volume of COVID-19 test orders. Jensen said the experience benefited the company.

“We learned that we can be nimble, that we can do things rapidly and still do them well,” he said.

By March 11, more than 4,200 people worldwide were reported to have died due to COVID-19, and the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. That same day, Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert tested positive, and the NBA suspended the season. Within days, states across the country began to implement shutdowns, and Utah was no exception. Gary Herbert, then governor of Utah, called for public schools to close for two weeks on March 16, but they would remain closed through the end of the school year.

“When COVID first hit, our testing volumes went down by over 65%. My main mission was to keep the company together and not have to let anyone go. Our employees are number one. The executives decided to take salary cuts to make sure that ARUP’s workforce and the company were intact when life returned to normal,” Perkins said. People united in the mission to serve patients and keep ARUP going. Many employees also offered to take pay cuts and fill in wherever they were needed.

ARUP faced many challenges in early 2020, including how to ensure the health and safety of employees required to be on-site, how to navigate the uncertainties of childcare, and how to keep morale up. “Trying to support our employees as much as possible was really the primary focus of the Executive team through much of COVID,” Perkins said.

On March 15, the first ARUP employee was diagnosed with COVID-19. Immediately, the ARUP Family Health Clinic, which provides primary care for more than 12,000 patients, shifted toward telemedicine as much as possible. The clinic worked closely with Corporate Safety and Information Technology teams to develop a COVID-19 reporting tool to track and organize employee cases and to moderate risk and exposure. As cases increased, the clinic partnered with the Facilities Department to build an on-campus specimen collection site for employees and their families, keeping the labs and facilities safely staffed.

Delgado, now ARUP executive vice president and the vice chair and chief of the Division of Clinical Pathology at the U, recalled vividly the mission to protect the workforce’s health and their jobs.

“I remember with so much gratitude how quickly ARUP was able to identify the tools to prevent any type of risk of exposure, how quickly we were able to offer the vaccine to individuals, and making the important decision to not lay anyone off,” Delgado said. “I am very proud of how we acted.”

On March 18, a 5.7-magnitude earthquake rocked Salt Lake City shortly after 7 a.m. while ARUP executives were meeting to discuss the COVID-19 response.

“Everybody immediately ran for cover under my desk. Eight or ten of us were cheek to cheek, wondering what was happening, and I was thinking, ‘On top of everything, now we have to deal with an earthquake?’ The gravity of the situation had us all nervously laughing,” said Delgado.

ARUP struggled with supply shortages but used research and innovation to create its own solutions. When a shortage of the media needed to transport specimens in test collection kits occurred, ARUP’s Reagent Lab moved quickly to formulate a saline transport media for COVID-19 testing. They also developed their own media, ARUP Transport Media™, to use as an alternative to universal transport media (UTM) when the world’s only supplier of UTM was unable to meet global demand.

ARUP also utilized the expertise of its researchers to identify solutions. An ARUP and University of Utah study determined that saliva specimens were as effective for detecting SARS-CoV-2 as the deep nasal swab specimens that were used initially. This research made it possible for ARUP to develop and launch a COVID-19 test that used saliva specimens, rather than hard-to-acquire nasopharyngeal swab specimens.

ARUP was sharing knowledge and sharing supplies. Adam Barker, PhD, then director of R&D, said he and Michael Bevan, vice president of supply chain and manufacturing operations, were driving around at night dropping off testing kits and reagents to hospitals because they had run out.

“Our focus was and is patient care. We were basically making sure that all labs, no matter who it was, were running, so everyone’s patients could get the testing they needed,” Barker said. Once ARUP scaled up testing, was in a groove with hybrid work, and had navigated the impact of COVID-19 on the bottom line, Perkins put the focus on making testing the most effective possible with automation and a state-of-the-art new building.

2021: Building 4 Opens

ARUP’s newest 220,000-square-foot building opened in 2021 and increased the company’s square footage by 45%. Seeing the need for continued growth, Perkins reactivated plans for the space shortly after accepting the CEO role and saw the project through to completion. The new building includes the Mountainside Café, Specimen Receiving (SR) and Specimen Processing operations, Mass Spectrometry Labs, automated Chemistry and Immunology Labs, and an entirely new track automation system.

The automation system allows for groups of 20 specimens to be transported in a single rack. The previous system moved one specimen along the automated track at a time. Automation also improved workflow and decreased turnaround times in the expanded Automated Core Lab, bringing manual touches down from 26 to eight. All areas of SR are centralized on the fourth floor, creating efficiencies.

“Our advanced automation has already allowed us to achieve Six Sigma standards, particularly in the area of number of lost specimens,” said former Operations Director Clint Wilcox, who oversaw the automation project.

Hidden above ceilings, tucked into floors, and even in a tunnel are mechanical, electrical, piping, and other flexible systems that also allow for scaling up and adaptation. To ensure laboratories can operate 24/7 without disruption, redundancies are built into the electrical, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. The sophisticated ventilation system exchanges the air within the labs with fresh air up to 14 times an hour to ensure specimen viability and for the benefit of laboratorians. A total of 18,500 square feet of windows allows for plenty of natural light and mountain views.

“In designing this building, we absolutely aimed to create an environment that would increase happiness and satisfaction among our employees,” said Jonathan Genzen, MD, PhD, chief medical officer. “If our staff is happy, we collectively accomplish great things.”

The Mass Spectrometry Labs include three separate chemical control areas to ensure safe use of chemicals and include 120 mass spectrometers, which demand an enormous amount of power. A custom exhaust system extracts heat from the equipment, providing for more accurate and reliable testing for patients.

Today, ARUP owns eight buildings in Research Park that include more than 65 labs and encompass 750,000 square feet of physical space. ARUP has intentionally kept most of its nearly 4,300 employees and labs centralized.

“We have seen how other reference laboratories that are spread out across the country are fraught with problems involving lost specimens,” Theurer said. “It is a competitive advantage to have testing in one place, and it also allows for in-person collaboration among our experts.”

*Six Sigma quality is a method to identify defects in a process and eliminate them to get as close to zero as possible. A typical Six Sigma goal is 3.4 defects per million opportunities.

2023 and 2024: New Business Units Formed

ARUP has seen tremendous growth during the past 40 years and has expanded from about 100 employees to more than 4,300, from just a few tests to more than 3,000, and from one building to eight. The company has started to adopt a new multidivisional corporate structure to respond strategically to its growth. Part of its strategy involves creating new business units to ensure focus on innovation and the university, from which the company began.

The ARUP Institute for Research and Innovation in Diagnostic and Precision Medicine™ (R&I Institute) was formed in 2023 to accelerate groundbreaking diagnostic and prognostic technologies to drive life-changing innovation.

“Their whole task is to partner with other companies developing cutting-edge technologies so we can develop those technologies and bring them right into healthcare systems,” Theurer said.

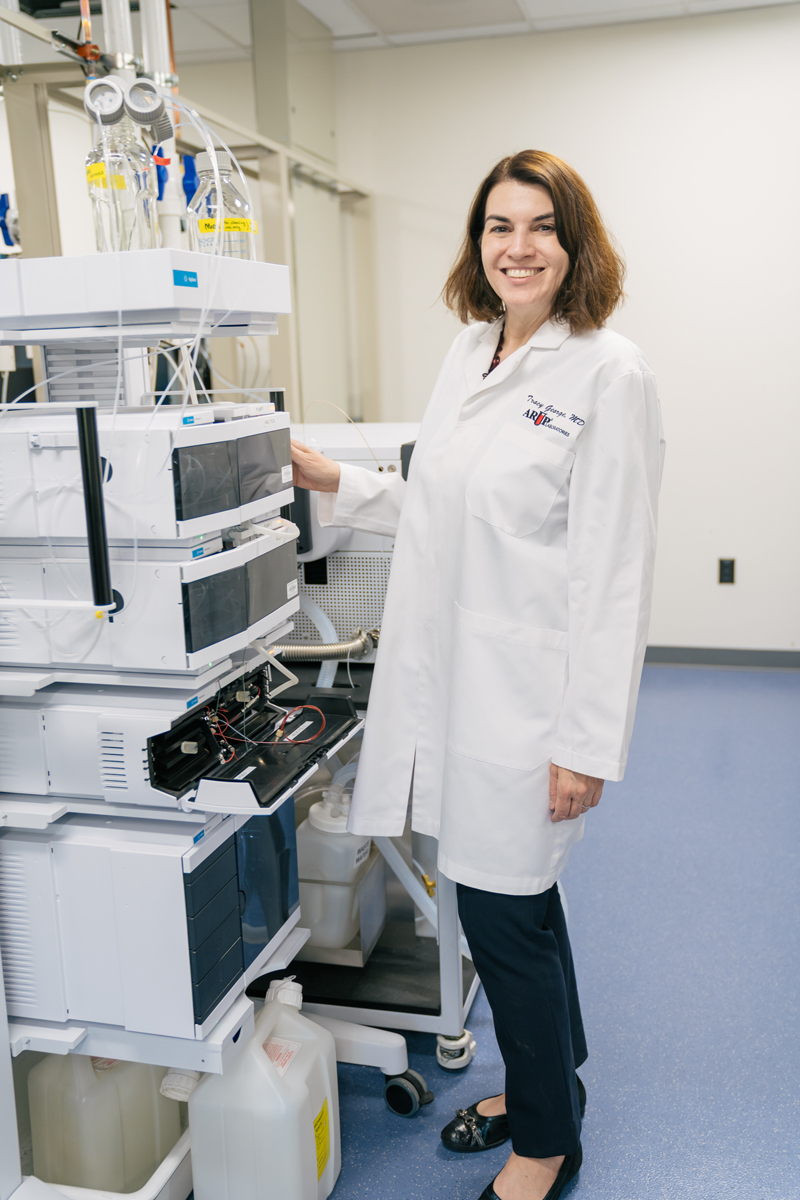

Led by Innovation Business Unit (IBU) President Tracy George, MD, who is also ARUP’s chief scientific officer, the unit includes R&D, the R&I Institute, the Clinical Trials group, and the PharmaDX group, which is focused on development of companion diagnostic tests to accompany novel pharmaceuticals. One such test is AAV5 DetectCDx™, the first FDA-approved companion diagnostic immunoassay.

The Clinical Trials group provides clinical research organizations, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) manufacturers, and clinical and academic trials and projects with access to ARUP’s broad clinical test menu.

The establishment of the R&I Institute as an entity dedicated to innovation signaled a new era as ARUP moved to intensify its efforts to accelerate invention and discovery.

“We are looking five and 10 years down the road to develop partnerships, technologies, and laboratory tests that will benefit patients and healthcare systems. My team is smaller and hyperfocused on the long game, and that allows us to be extremely nimble. We know we will have some failures, but we will move on quickly and find many successes,” George said.

ARUP’s University Business Unit was formed in April 2024 and is led by President Dan Albertson, MD, who is also division chief of Anatomic Pathology and Solid Tumor Molecular Pathology. It is made up of all ARUP laboratory operations within the University of Utah Health system, as well as ARUP Blood Services. Albertson said the unit’s goal is continuous improvement both in patient care and in operational efficiencies.

“It is important for me personally to approach every leadership position with service to others at the forefront,” Albertson said. “As I help lead this new business unit, providing the highest quality laboratory testing to U patients will be the primary focus.”

Work Worth Doing

Patients have been ARUP’s focus from the beginning. With more than 20 million specimens now being tested annually, ARUP is impacting the care of nearly 17 million people every year. They include patients such as Hamilton’s late husband, who was diagnosed with melanoma shortly after her retirement. Hamilton said next generation sequencing (NGS), performed at ARUP, pinpointed his cancer’s genotype, and as his disease progressed and the medicine improved, clinicians could direct targeted therapy.

“My husband passed away after seven years, which is a tremendous time to survive with stage IV melanoma. It was because of the tests, the people behind the tests, and understanding what was working and not working,” Hamilton said. “The work that we do here is important. It’s work worth doing.”

As ARUP looks ahead, there are plans for growth, including additional buildings, and a sense of gratitude in Theurer. “Not many companies last 40 years. It’s worth marking the moment because ARUP is thriving. Some of the most brilliant minds in the world are right here, and with them, our success is ensured. I’m honored to be part of it.”

Andy Theurer is named CEO after more than 30 years with the company. George is named president and continues in her role as CMO.

Andy Theurer is named CEO after more than 30 years with the company. George is named president and continues in her role as CMO. ARUP opens its newest building, Building 4. Every aspect of the new building has been carefully designed to optimize large-scale laboratory operations and position ARUP for future growth.

ARUP opens its newest building, Building 4. Every aspect of the new building has been carefully designed to optimize large-scale laboratory operations and position ARUP for future growth.